Resilience ~

: the capability of a strained body to recover its size and shape after deformation caused especially by compressive stress

: an ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change

When we look at business, psychology, or sociology the concept of ‘recoverability’ is a key component in measuring the health and effectiveness of an organization, an individual, or a society. In dealing with unpredictable or unexpected events, the most successful organizations, people, and societies are those able to adapt and create novel solutions to novel circumstances. Elements of the successful actors are creativity, commitment, confidence, experience, and talent but in the case of shocking events the most common term for this collection is resilience.

When we look at business, psychology, or sociology the concept of ‘recoverability’ is a key component in measuring the health and effectiveness of an organization, an individual, or a society. In dealing with unpredictable or unexpected events, the most successful organizations, people, and societies are those able to adapt and create novel solutions to novel circumstances. Elements of the successful actors are creativity, commitment, confidence, experience, and talent but in the case of shocking events the most common term for this collection is resilience.

The black swan is the typical example of a completely novel event. European explorers had never seen a black swan as that genetic mutation did not exist in Europe. In 1697, when Dutch explorer

Willem de Vlamingh discovered black swans in Australia, it was something

never before considered. This term has come to be used to describe unpredicted events ranging from natural disasters to terrorist attacks and is used extensively in the risk management field. Detection and deterrence in personal security, and prediction and risk mitigation to businesses are very different from the ability to react effectively to novel inputs.

This phenomena of extraordinary shocks to business systems is studied extensively in risk management with

supply chains being the primary target, and easiest to quantify metric, of redundancy and alternate capabilities. When an 8.9 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Japan in March of 2011, Honda,

Toyota and

Nissan were all forced to shut plants in the affected region. While Honda and Toyota were massively impacted well into the fall, Nissan had recovered its production capability largely by April, and completely by July. They had invested in redundant production capability and created a globally dispersed, redundant product sourcing and assembly capacity. Ultimately, Nissan gained a long-term increase in total market share. It is largely considered the model for effective supply chain resilience.

At an individual level, it is usually studied by psychologists looking at the impact of traumatic events after the fact; most frequently in the study of

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. More recently, organizational psychologists are starting to attempt to develop quantifiable programs to develop resilience in a variety of aspects including management and leadership. Military training has been attempting to build resilience into tactical leaders since the dawn of armies. From a general security perspective, we are not at great risk from what we can predict, we are at great risk from what we cannot predict. The only mechanism we have to defeat black swan events is resilience. From an individual security perspective, what we should be concerned with is how we can create resilience in individuals.

As we look at the ability to forecast or predict events from an individual perspective, the concept of detection and deterrence can become even more challenging. Organizations have the ability to hire professionals to evaluate supply chains, identify critical risks and develop plans and take action to mitigate those risks in an academic setting. Most private citizens do not have a full time security detail conducting the equivalent of those skills for them, and further, the consequences are personal. It makes us even less likely to account for the potential black swans in our personal lives then in our professional.

Worse, we tend to overestimate our abilities in the personal security arena where we are rarely measured. While the risk of being fired is substantially stressful, it is not the same as the risk of being injured or killed. That fear often translates in to denial. Despite the fact that most citizens have little to no experience or training that enables them to be more effective then “average” in avoiding or deterring threats, when polled, most consider themselves “above average”. We see this common belief in a variety of skills and most drastically in that 85 - 90 % of Americans believe they are an “above average” drivers… Worse, our misconceptions are reinforced that we are superior in our ability to avoid violence due to the relatively infrequent occurrence of violent attacks (or car accidents) that would provide us evidence contrary. 2/3’rds of our society will never have their assumption challenged, but more then 32% will…

If we consider the skills required to deal with expected scenarios, they are quite different then when dealing with novel scenarios. It is the difference between being taught

what to think as opposed to being taught

how to think. Expected scenarios are studied, quantified, and measured. The inputs and outputs can then be evaluated and placed on a scale of positive vs. negative consequences and those inputs prioritized accordingly to maximize positive outcomes and minimize negative outcomes. We can then teach people what to do when they see relevant inputs; in other words, what to think and do.

In dealing with completely novel scenarios, by definition, we will not recognize the inputs, and will have no idea what the most likely outcomes to our actions will be. Time and time again, in studying responses to novel events, we find that people, organizations, or societies that have a broader scale or wider range of abilities and skills to call on, perform better. The simplest example is the supply chain as discussed with Nissan. They had more diversity in production, and were able to leverage that to recover quicker, ultimately achieving a long term advantage over their competitors.

On the individual level, psychologists have proposed that developing strengths are a more useful endeavor in determining the long-term success of individuals. The thought is that individuals will gravitate towards fields in which they are competent, and be judged as successful based largely on their ability to apply that core competency. In dealing with predictable environments like employment, developing strengths is a more productive allocation of time than attempting to improve on irrelevant shortcomings. The problem arises when confronted by novelty. Those with a broader range of experiences have proven to be clearly superior in finding solutions to novel challenges then those with more specific skill sets.

As we look at threats to organizations or individuals, we see a list of potential inputs, appropriate responses all with the goal of mitigating the risks we know about. Those are not the risks that tend to cause truly negative outcomes. It’s the ones we didn’t see coming that consistently take the largest toll. Developing resilience requires a commitment to the development of individuals in skills and experiences that may not directly impact their day-to-day activities. For an organization to justify that type of investment is rare, and individuals are equally unlikely to decide to improve skills they have yet to need and see no short-term benefit to developing.

The reality is that as we look across existential threats to organizations or individuals, resilience is the key determinant of survival when these novel events occur. Next month, we’ll take a look at exactly how critical resilience is to personal security. Further, why it so difficult for us to predict negative outcomes in our personal lives; and we’ll take a look at how we can build resilience into individuals, leadership teams, and organizations as whole. Resilience is a key component to the safer communities we all desire to live in!

Author - Patrick Henry

In protecting a business, we make it less subject to competition and subsequently less efficient over time. This inefficiency invariably results in underutilized resources and waste. Charles Koch and I do not agree on many social issues but his take on corporate welfare is dead on. Corporate welfare is eroding American competitiveness as surely as long-term welfare is eroding the competitiveness of the individuals receiving it. When we exempt institutions from paying taxes, we burden other productive enterprises with making up the difference, which removes resources that productive enterprises could use to create jobs and opportunity.

In protecting a business, we make it less subject to competition and subsequently less efficient over time. This inefficiency invariably results in underutilized resources and waste. Charles Koch and I do not agree on many social issues but his take on corporate welfare is dead on. Corporate welfare is eroding American competitiveness as surely as long-term welfare is eroding the competitiveness of the individuals receiving it. When we exempt institutions from paying taxes, we burden other productive enterprises with making up the difference, which removes resources that productive enterprises could use to create jobs and opportunity. Our founding fathers were brilliant, but, in this case, they got it wrong: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness are not unalienable rights. Those concepts are incomprehensible to much of the world’s population who are simply content to avoid conflict and do only what they are told. That incomprehensibility applies to many of our citizens right here in America. What makes America Great is that Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness are privileges that each American has access to, and the opportunity to put to use every day of his or her life. Segregation, special treatment and exemptions are eroding the value of those ideals.

Our founding fathers were brilliant, but, in this case, they got it wrong: Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness are not unalienable rights. Those concepts are incomprehensible to much of the world’s population who are simply content to avoid conflict and do only what they are told. That incomprehensibility applies to many of our citizens right here in America. What makes America Great is that Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness are privileges that each American has access to, and the opportunity to put to use every day of his or her life. Segregation, special treatment and exemptions are eroding the value of those ideals. This article will answer a reader’s question debating the importance of front sight focus. While addressing this topic, I’ll also cover the mechanics of the human eye and the different types of pistol sights.

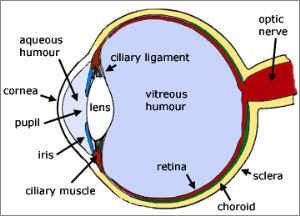

This article will answer a reader’s question debating the importance of front sight focus. While addressing this topic, I’ll also cover the mechanics of the human eye and the different types of pistol sights. Light enters the pupil which acts as an aperture controlling the amount of light passing through two lenses which posit the focused image on the retina. This image is then sent via the optic nerve to the brain. The light passing through the eye is "focused" or sharpened by the two lenses. The outermost lens is the cornea, which is fixed, and the innermost is the crystalline lens, which is variable. Altering focus from near to far objects requires a change in optical power which is controlled by the crystalline lens. In order to focus on a distant object, the ciliary muscles relax and flatten the curvature of the crystalline lens. Conversely, the ciliary muscles contract to create a bulge in the crystalline lens which causes greater refraction allowing focus on close objects.

Light enters the pupil which acts as an aperture controlling the amount of light passing through two lenses which posit the focused image on the retina. This image is then sent via the optic nerve to the brain. The light passing through the eye is "focused" or sharpened by the two lenses. The outermost lens is the cornea, which is fixed, and the innermost is the crystalline lens, which is variable. Altering focus from near to far objects requires a change in optical power which is controlled by the crystalline lens. In order to focus on a distant object, the ciliary muscles relax and flatten the curvature of the crystalline lens. Conversely, the ciliary muscles contract to create a bulge in the crystalline lens which causes greater refraction allowing focus on close objects.